|

Gallup goes to war

Residents remember rationing, shortages and

fear of bombs during World War II

Gallup's main street, Route 66, is seen in the summer of 1941 before

America entered World War II. [Photo courtesy of the Gallup Museum

and Nello Guadagnoli]

By Zsombor Peter

Staff Writer

|

U.S. Army troops wade ashore on Omaha Beach during the D-Day

landings June 6, 1944. They were brought to the beach by a

Coast Guard manned LCVP [Photograph from the U.S. Coast Guard

Collection in the U.S. National Archives]

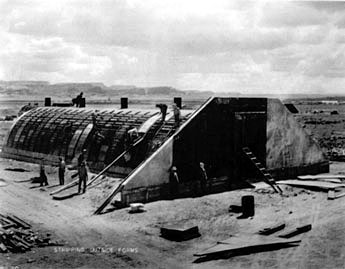

Munition bunkers were constructed at Fort Wingate to store

ammunition destined for U.S. troops in Europe, Africa and

the Pacific during World War II [Photo courtesy of the Gallup

Museum]

|

GALLUP — In the months leading up to D-Day, Madeline Jennings,

at the age of 5, just couldn't understand why she had to mix packets

of food coloring into the colorless Oleo margarine her grandmother

would buy.

"My grandmother would get the Oleo in these little packets

and we would get the white margarine and squish it together,"

she recalled more than six decades later. For their effort, the

family would end up with a yellow goo that was supposed to look

something like butter.

"That was the one thing I would always remember, because I

could never figure out why," she said.

As she later found out, all the real butter was going to the U.S.

military. The country had declared war against Japan Dec. 8, 1941,

the day after the Imperial Navy launched a surprise attack on Pearl

Harbor, decimating the U.S. fleet stationed there and killing more

than 2,400 Americans. Almost 2 1/2 years later to the day, on June

6, 1944, Allied forces would launch their own invasion on the beaches

of Normandy, the start of the final push that would drive Hitler's

forces out of Western Europe.

These days, President George W. Bush talks of a "war on terror."

Except for those with family members stationed in the hot spots

of that war, and especially the few thousand families who have lost

loved ones, few Americans have felt its direct impact. Today, on

the 63rd anniversary of D-Day, that experience stands in stark contrast

to a county at total war.

Running on empty

To help fuel one of the greatest military buildups of modern times,

the federal government rationed everything from sugar to gasoline.

Basics that weren't rationed became increasingly hard to come by.

Auto plants stopped making cars so that the part and labor could

be put to use churning out tanks and battleships. Everyone was called

on to save and turn in whatever tin they could find.

"We had to do the best we could with what we had," recalled

Hershey Miyamura. "Everyone had to go through some kind of

hardship."

Remembered most as a Medal of Honor recipient for his service in

the Korean War, Miyamura enlisted when the Second World War broke

out, but never saw combat. He was five days out from Naples, Italy,

when the war ended. In 1941, he was working as a mechanic for the

Gurley Motor Company.

With auto plants from coast to coast devoted to the war effort,

Americans had no new cars to buy. Even the bits and pieces needed

to keep the ones they had going grew scarce. A young mechanic had

to learn fast.

"We couldn't get parts to fix the cars," Miyamura said.

"We learned a lot; we had to improvise."

Wendell Briggs, whose family moved to Gallup a year before the attack

on Pearl Harbor following his two older brothers, who came to build

the Fort Wingate weapons depot, remembers what it took to draw out

the life of a tire.

"You had patch on top of patch on top of patch to make them

last," he said.

By D-Day, Briggs was in San Diego learning to drive landing craft

for the Navy. He would put those skills to use in the Pacific, where

he turned 19 during the battle of Okinawa.

When the war broke, he was working for the Navajo Chevrolet Company

in Gallup, manned the filling station by day and servicing cars

in the afternoon. He remembered the hard-up families that would

pass through town chasing the promise of a steady job in California.

But mostly, with a ration on gas the idea was to save both gas and

the rubber in their tires ( by forcing people to drive less ( people

mostly stayed put.

"People hardly went anywhere because they didn't have the equipment

or anything else," he said.

Where's the beef?

People had to change their eating habits as well. Butter was just

the beginning.

"Everything was rationed," Briggs said, "practically

everything: flower, sugar, spices,"

Families received a set number of ration cards for the month. But

they didn't always last.

"Sometimes we'd run out, and you just had to make-do,"

he said.

But the rationing might not have been so hard on the Briggs family

was it was on others. They were used to squeezing by on very little

even before the war.

"So the rationing wasn't all that bad on us because we never

had all that much in the first place," he said.

Gallup native Frank Gasparich, who celebrated his 6th birthday about

a month after D-Day, remembered eating a lot of beans during the

war. Rationing also cut into the public's meat supply.

"We didn't have any steak or nothing like that; that was a

delicacy," he said. "But chili was always in."

With sugar also being rationed, they all remembered a short supply

of dessert as well.

"I liked sweets and all that, and I couldn't get near what

I wanted," Miyamura said.

"You couldn't find chocolate," Gasparich added, "It

had to go to the boys overseas."

Gasparich remembered doing without regular toilet paper even. They

made-do with the "funny pages."

"If there was a Sears catalog around," he added, "we'd

use that."

But families didn't necessarily stick with the ration cards they

got. A sort of gray market evolved. If a family didn't use up all

its cards for one commodity but needed more cards for something

else, Miyamura said, they'd trade.

By some accounts, adjusting to the war was a little easier on the

reservation, where families grew and raised more of their own food.

Rose, a Navajo woman who offered only her middle name, grew up in

Sanders, Ariz. She was in her early teens during the war and recalled

her mother simply giving her ration cards away. More than anything,

though, she remembers the day Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

Her mother was returning from a trip to Gallup and drove up to Rose

and her sister in a frenzy: "She was yelling, 'Pearl Harbor

was bombed. Japan bombed us.' And my sister, she said, 'It sounds

like she thinks it's our fault.'"

What she doesn't remember is ever doing without enough food. Her

father was a farmer and mutton was always in good supply.

Tin can alley

But if the government was forcing most families to cut back during

the war years, it was also asking them to chip in.

Tin and aluminum became especially valuable, and everyone was asked

to turn in as much as he or she could find, even if it meant scraping

the foil off gum and cigarette wrappers.

"We had to sit down, scrape off the aluminum and make them

into balls," Jennings recalled.

"It took a lot of doing ... but everyone was doing it, and

us kids would get together and pool our resources," she added.

"Sometimes there'd be contests in the school for who could

turn in the biggest (ball)."

Did Jennings ever win?

"Heck no," she said. "The biggest mine ever got was

(the size of) my fist, and my fist wasn't very big."

People weren't just asked to chip in, Gasparich recalled; they were

expected to. The family would squash its used tin cans, put them

on a string, and wait for a collector to pick them up.

"This guy used to come by for tin cans," he said. "If

you didn't have any ... he'd get mad. I guess he had a quota to

meet."

At least Gallup didn't have to live in constant fear of another

Japanese surprise attack, as many along the West Coast did. But

living next to a weapons depot wasn't a comfort either. Miyamura

remembered his family covering up the windows at home once or twice,

to confuse the bombers in case they showed up.

But even as a Japanese American, Miyamura said he largely felt out

of harm's way in Gallup. The U.S. government labeled them all "enemy

aliens" and sent many off to internment camps for the duration

of the war. The 25 or so families in Gallup were allowed to stay

put, and Miyamura remembered them suffering no more discrimination

during the war than before.

"My friends all stood up for us," he said.

Even so, the war called on every American somehow, whether abroad

or at home. It marshaled the resources of an entire nation and left

no American untouched.

Jennings no longer has to color her margarine to make it look like

butter. She can even get the real thing now. But to this day she

can't stand to throw things away. The war taught her to hold on

to things and squeeze the last bit of life out of everything. It's

a lesson she's never forgotten.

During those lean years of the Second World War, she said, "it

was just a way of life."

|

Wednesday

June 6, 2007

Selected

Stories:

Chief,

some officers to meet; Honeyfield urges talks with 'disgruntled'

cops

Teens

accused of firing at police

Rally

to roar into Grants; Fire and Ice Bike Rally named among top biker

events

Gallup

goes to war; Residents remember rationing, shortages and fear of

bombs during World War II

Deaths

|